Shutterstock

Wrote about the history of star designs for Shutterstock blog

Stars have fascinated artists, historians, and scientists for thousands of years. Understanding why, helps us better integrate this imagery into new work.

The Timeless Influence of Stars

Stars have draped themselves across our night sky for the entirety of the planet’s existence. Humans have gazed up at them thinking dreamy thoughts, astronomical thoughts, and have launched thousands of wishes at them.

People have recorded celestial events since the days woolly mammoth roamed the earth. They are also how we’ve managed to navigate across water and land in the dark.

Stars are also wedged firmly into our language. We call highly regarded humans, start (art stars, movie stars), and talk of being starry eyed, having star crossed lovers, or of things being written in the stars.

Ever since humans looked upwards, we’ve noticed and anthropomorphized star patterns to help remember them.

A 32,000-year-old ivory tusk table t was found in Germany, carved with a human figure whose arms and legs are in the position of the Orion constellation. The other side of the tablet shows notches that are thought to be a pregnancy calendar.

Early star patterns appear elsewhere, including cave paintings from France (Lascaux) that are 15,500 years old. Scholars think these depict a historic comet strike, a drawing of a rhino and a horse (representing constellations Taurus and Leo.)

Our Notion of Time Comes from Stars and Planets

Stars help us understand time and space. We know where we are geographically, based on the night sky. We know what time of year it is by climate and day length—things governed by our distance from the sun, which is, as we know, a star.

Early Scots in 8,000 BCE created a monument to display lunar and solar movements (a clock of gigantic proportions). This may be the oldest relic of time measurement—which by the way predates Stonehenge.

There is also a relic called the Nebra Sky Disk from the Bronze Age which was part of an early lunar calendar. It is a circular wafer of metal displaying a gold moon, sun, and stars scattered in the pattern of the Pleiades constellation.

And, in Turkey there is a pillar from 1,100 BCE which was etched with images of a scorpion, a bear, and a bird, connoting the constellations of Scorpio, Virgo and Pisces.

The more you think about calendars and the measuring of time, the more they relate to stars—what is a month or a year, what are seasons if not connections to the sun and moon?

Where would agricultural planning come from and how would family planning be understood (menstruation), without the study of celestial positioning?

Mayan and Egyptian calendars relied on stars; Indian wall paintings depicted comets. The word Monday is from moon and Sunday is from sun. Stars are inseparable from our lives.

Diverse Ways to Illustrate Stars

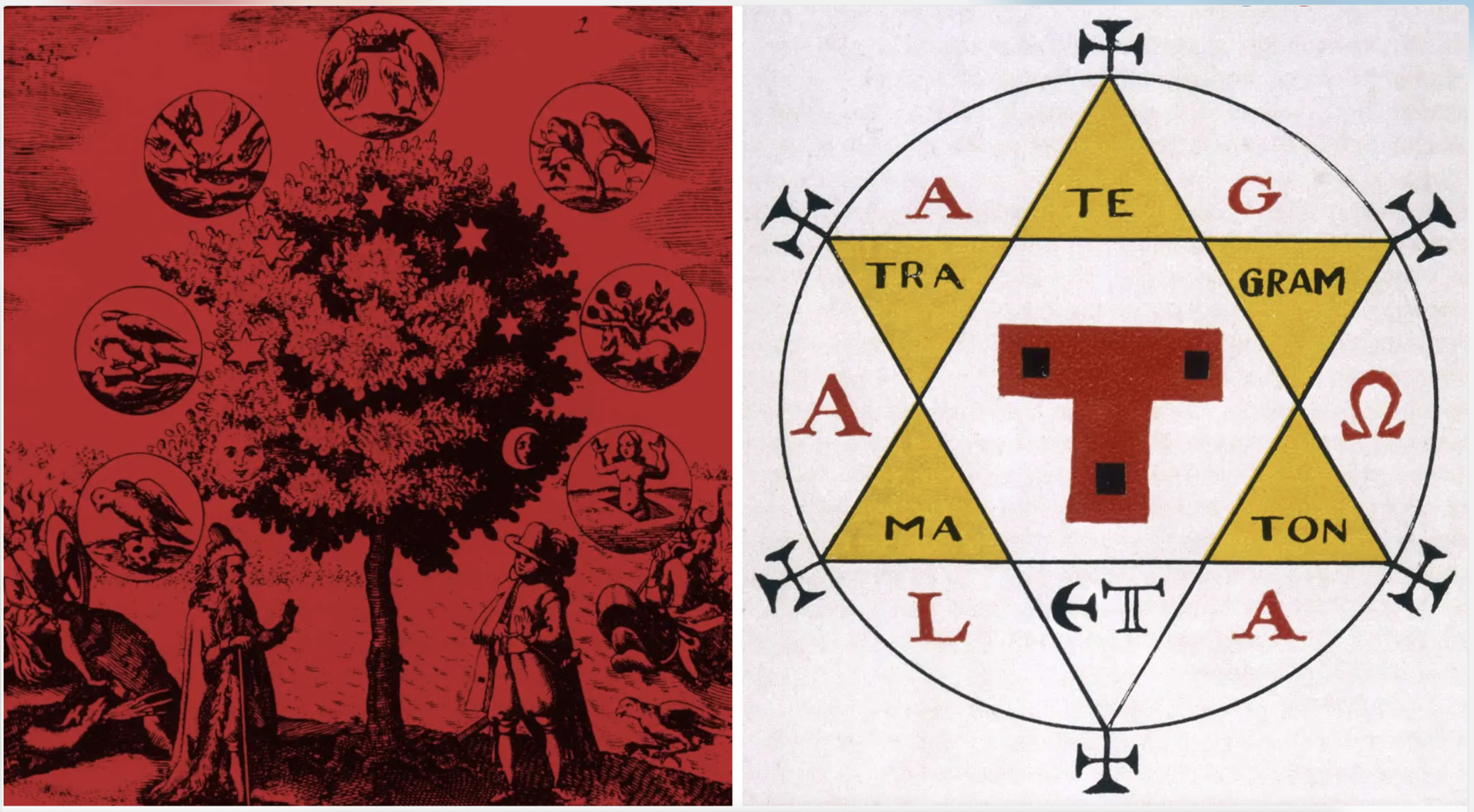

The depiction of stars did not wait for science. While telescopes arrived in the 17th century, celestial bodies seen with the naked eye were painted much earlier into astronomy charts, sailor’s maps, carvings, and other useful navigational tools. Stars appeared in a host of shapes and formats: painted as tiny dashes, hairy orbs (those were most likely comets), pointillist dots, loose hashmarks, hazy blobs, geometric figures of four, five, six (or more) points.

Ancient Egyptian tombs show a propensity for four and five-pointed stars. Millennium old Sumerian pottery often used the five-pointed variety. The eight-pointed Star of Lakshmi (two squares overlapping) is an important star in Hinduism. It’s also prominent in Chinese history.

The Greeks invented asterisks, the star symbol made from lines that intersect in the middle (asteriskos means little star).

Astronomers and ship captains spent much time perfecting star maps, but artists were enthralled by stars for aesthetic reasons. In the 1300s, Italian painter Giotto di Bondone used copious amounts of a pricey blue pigment more expensive than gold, to depict a deep azure sky full of stars, on the ceiling of the Arena Chapel.

In the 1400s tarot card decks featured pentacles which are stars—the name came from pentagram, a five-pointed star.

Stars Move Into Abstract Contours

By the 1800s, the star symbol was up for reinterpretation. Many European artists began portraying stars in ways that were not the usual glowy or pointed orb or pentagram or hexagram.

In 1889 Vincent Van Gogh painted stars in thick swirls in The Starry Night. In 1905 Henri-Edmond Cross painted a starry sky using a fantastic mass of dashes. In 1917, Georgia Okeeffe interpreted the night sky in Starlight Night and gave us an altogether modern version of stars, a blanket of dark blue checks. Henri Matisse in his collage Icarus (1947) cut out dangly star shapes from yellow paper.

Humans Wanted to Cadge the Star’s Stature

Stars in many parts of history were seen as mighty, sometimes mystical. They were highly regarded and given a connotation of authority.

People felt stars represented power, and even sometimes magic. Witchcraft has a long association with star shapes, and the word hex comes from hexagram, a six-pointed star. In Ancient Egyptian paintings, star symbols were on the fronts of warriors helmets. In Medieval times, knights wore them on their shields.

Much later in the 18th century in America, stars arrived as sheriff badges in the west. These badges (usually six pointed stars) signified someone of authority. Being made of metal they also glinted in sun or moon light, which helped with visibility. But, not every town was prosperous enough to afford metal in those days. Early sheriff badges were often crafted at home, snipped from a tin can or scrap metal.

As nations designed national flags, stars were often added to them (72 countries included stars). The U.S. police force and the U.S. military, integrated star insignia into their uniforms.

The star of life became the symbol for emergency medical services (the blocky six-legged star with a snake in the center).

We Are Stardust

While governments and organized bodies embraced stars, these symbols have always been irresistible to philosophers and poets as well. There may be more poems about stars than actual stars in the sky.

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote, in Falling Stars

Do you remember still the falling stars

that like swift horses through the heavens raced

and suddenly leaped across the hurdles

of our wishes—do you recall? And we

did make so many! For these were countless numbers

of stars: each time we looked above we were

astounded by the swiftness of their daring play,

while in our hearts we felt safe and secure

watching these brilliant bodies disintegrate,

knowing somehow we had survived their fall

While it is easy to ride along on poetic lines about stars, it is easy to forget that we are physically made of stars. We are stardust. Planetary scientist Dr. Ashley King said,

”It is totally 100% true": nearly all the elements in the human body were made in a star and many have come from superonovas.”

Technically, we are all stars already.